The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), an independent agency of the Federal Reserve Board, claimed it was seeking to “jumpstart competition” with its October 22, 2024, final rule on consumer data access in accordance with a Dodd-Frank consumer data access provision.1 The Bureau’s strong advocacy on consumer rights and identity ownership convey its philosophical convictions and gives us some insight into the design patterns of the rule.2

At its core, the rule is designed to make financial institution (FI) data more portable for consumers, so they are not tied to any single institution. Foundational to this approach is the rational application of secure application programming interfaces (APIs) that link banks to data aggregators together with their third-party service providers. This architecture of linked data is fundamental to the open banking/open finance concept. A haphazard implementation of open banking/open finance could lead to greater risks both by exposing more of an FI’s operational technology and infrastructure to third parties (thereby creating a broader attack surface for threat actors), and by revealing sensitive bank data to bots and artificial intelligence (AI) agents. Critics of the final rule argue that key omissions in the final rule will inevitably lead to a haphazard implementation.

The rule’s emphasis on standardized APIs for data transmission aims to improve security compared to older methods of sharing customer data such as screen scraping, but it also requires FIs to develop and maintain secure interfaces that can withstand potential cyberthreats. Theoretically, through open banking, financial information will flow among various parties in the financial services ecosystems, including banks, fintechs, data aggregators, and consumers, facilitated primarily through APIs.

Prescriptive compliance requirements for interfaces (aka, APIs) are given in the final rule for developers and consumers. However, the technical implementations of these APIs will be left to authorized standard-setting bodies (SSBs) overseen by the CFPB. My last blog article covered SSBs and an application from the Financial Data Exchange (FDX) to be authorized as an SSB in some detail. In this article, I outline key provisions of the new rule impacted by the “interfaces” language to flush out the implications for API design specifications.

The entire FI ecosystem supply chain will be impacted by these rules. These impacts will present a double-edged sword.

Omissions of Final Rule: One Edge of the Sword

Several groups within the regulated community have been highly critical of the final rule, with concerns centering on an assertion that the CFPB has overstepped its statutory authority and that certain provisions of the final rule are arbitrary and capricious. Plus, critics argue there are key omissions in the final rule that could have helped stabilize the regulatory framework. These are primarily in the areas of liability for third-party access, user fees, and the introduction of transactions within the defined scope of data access. These elements will have important implications:

- Liability concerns: Lack of clarity about liability issues in the rule creates uncertainty for FIs, data aggregators, and third-party service providers. Without clear liability guidelines, FIs may be hesitant to share consumer data, fearing they could be held responsible for data breaches or misuse by third parties. This could slow down implementation and limit the effectiveness of open banking initiatives.

- Consumer protection gaps: The absence of liability provisions may leave consumers vulnerable if their data is compromised or misused after being shared with a third-party that they have authorized. Some critics argue that under the language of the final rule, third parties are not held to the same high standard for fiduciary-like responsibility that banks currently have. Therefore, it is unclear who would be responsible in such scenarios.

- Need for industry standards: The liability omission may prompt FIs and data aggregators to develop their own bi-lateral contractual agreements to address liability concerns. This could lead to inconsistent practices across the industry. This would have the opposite effect to that which the Bureau had been hoping (i.e., to “jump-start competition”).

- Prohibition on fees: The rule’s prohibition on charging fees for providing user data has significant implications. FIs will need to absorb the costs associated with developing and maintaining data-sharing infrastructure without the ability to directly recoup those expenses through fees. This could potentially impact their bottom line or lead to cost-cutting measures in other areas. While direct fees are prohibited, institutions may seek to offset costs through other means, such as increasing fees for other services or reducing interest rates on deposit accounts.

In addition, there is a strong sentiment among banks and insurers that the final rule does not adequately address their concerns about data privacy and security. Many institutions worry that they could face increased risks without sufficient protection against potential misuse of consumer data by third-party entities. This is especially true under a scenario in which a third-party is authorized by a consumer to make payments from a service provider that does not apply financial grade API (FAPI) practices using the FDX API standard. Finally, the schedule is seen by critics as being too aggressive, and it is argued that the final rule did not address several key points made by the over 11,000 commentors. These convictions are held so strongly by some critics that a lawsuit was filed one day after the final rule was published.3

Opportunities of the Final Rule: The Other Edge of the Sword

As noted above, open banking is the development of a new financial ecosystem based on connectivity among FIs and businesses, powered by APIs. Through the FDX API standard, banks are enabling data aggregators and fintech firms to integrate financial services into their customer proposition, providing access to bank data and delivering a broad suite of FI services via APIs. As a demonstration of widespread adoption of this industry-led, consensus-based standard, FDX announced that over 94 million customers are now using its API standard.

Open finance extends an FI’s offerings by leveraging a customer’s financial data to improve the customer experience and reduce administrative costs for processes such as account opening and loan and mortgage applications. Banks and fintech firms can develop innovative and personalized financial solutions in payments, lending, or personal financial management (PFM) through an open finance model. The CFPB’s design pattern, as expressed in the final rule, seeks to facilitate these types of integrations.

Theoretically, this will lead to an open economy. An open economy is an abstract end state in which an internet of finance is fully functional and frictionless for consumers in their access to financial services, their ownership and control of their own data and privacy rights, and their ability to pick and choose their FI and financial relationships. This would give them maximum portability of their identities. All these benefits for FIs, finance, and the economy must be operationalized. This is what FDX and its broad constituency have aimed to do for several years in advance of the CFPB rulemaking in an effort to align with other innovative (open) banking practices around the world. Proponents of open banking argue that the consensus-building process of the financial services community is leading the mandate by recognizing the market opportunities offered through a fully integrated consumer-centric system. The business opportunities are so vast that they far outweigh any compliance risk matters presented by the rulemaking.

Within this business and compliance context, the final rule provided very specific requirements for cybersecurity enhancements:

- Development of secure, standardized APIs and implementation of advanced API security solutions

- Enhancement of web application firewall capabilities

- Deployment of sophisticated bot management tools

- Strengthening of authentication in consumer identification and management systems

- Improvement of data encryption technologies

- Enhancement of third-party risk assessment and management processes.

The emphasis on next-generation firewalls, web application security, and APIs comprise the emerging web application and API protection (WAAP) market. We have covered this market in several previous reports since 2022. It is a perfect example of how market forces drive innovation.

In addition to reflecting natural market forces, the Section 1033 rulemaking has been an exercise in defining the institutional relationship between the CFPB and the SSBs (to date, only FDX) and the cybersecurity enhancements that need to be made to provide transparency, security, and data portability to FI service consumers. What are the key provisions in the rulemaking driving these cybersecurity enhancements?

Interface Design and Development: The Nexus

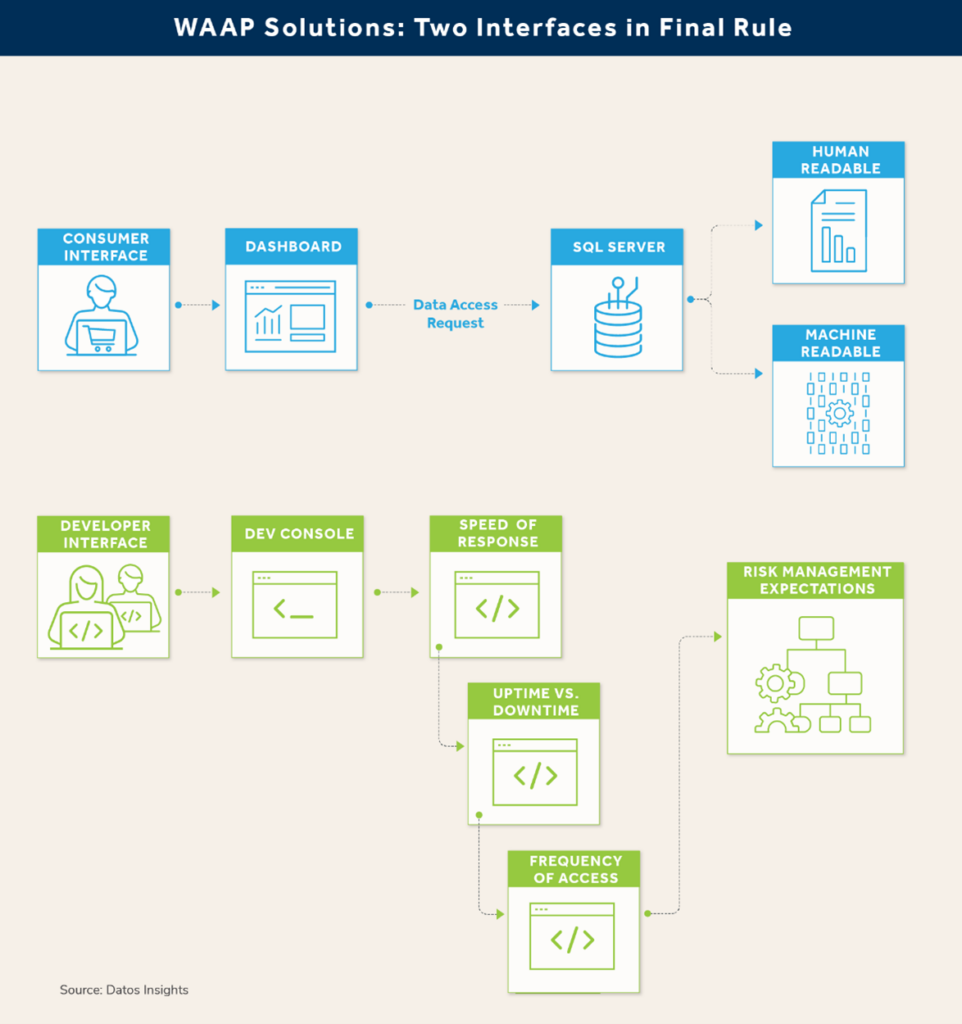

In the above image there are two double-edged swords that cross each another. In the subject rulemaking, we can say that the juncture of the costs and benefits of open banking and consumer data access falls at the interfaces of the digital constructs for enablement. In the language of the rulemaking, these are known as the “developer interfaces” and the “consumer interfaces.” The CFPB gave abstract guidelines and performance criteria for the construction of these interfaces as shown in the figure below. Note that I’ve labeled these as WAAP interfaces to encompass next-generation firewalls, the microservices of web applications, and the functionality of APIs.

Consumer Interface

The consumer interface must provide access to specific types of covered data, such as the following:

- Transaction information

- Account balance information

- Information needed to initiate payments

- Upcoming bill information

- Basic account verification information

Further, it must be performant for machine-readable systems and human readable, as shown in the figure.

Developer Interface

In contrast, the developer interface language established criteria for speed of response, uptime vs. downtime (measured in blocks of time by month), and frequency of access. The CFPB envisions these metrics as useful key performance indicators for assessing risk in the open banking architecture.

In response to concerns about the complexity and cost of implementing developer interfaces, particularly for smaller providers, the CFPB emphasized its commitment to technological neutrality. It introduced provisions allowing data providers to contract with service providers to maintain these interfaces. This approach is intended to reduce compliance costs by leveraging economies of scale while ensuring that the ultimate responsibility for compliance remains with the data provider.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the CFPB’s final rule reflects substantial stakeholder input and addresses various concerns, it firmly establishes requirements aimed at enhancing consumer access to financial data while fostering a secure environment for third-party access. Legal challenges may lead to some changes on matters of dispute, but the accelerating pace of technical innovation and the wide adoption by institutions and consumers alike indicate that there is a historical precedent that will not likely be reversed. As we navigate the complexities of the CFPB’s final rule, we must wield this double-edged sword with care, balancing the promise of enhanced consumer access and innovation against the potential risks that accompany such transformative change.

For more information on the CFPB rules and how your institution may be impacted, contact me at [email protected]. For more information on emerging issues relative to API security, check out the Datos Insights’ report Web Application and API Protection (WAAP): Market Landscape and Product Deep Dive, July 2023.

- Patterson, J and Chugani, S. (Feb. 14, 2024). AI and Privacy in the New Age of Open Banking. Business Law Today. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/resources/business-law-today/2024-february/ai-and-privacy-in-the-new-age-of-open-banking/ ↩︎

- https://www.cnbc.com/video/2024/10/22/cfpb-director-on-new-consumer-banking-data-rules.html ↩︎

- Forcht Bank, N.A., Kentucky Bankers Association, and Bank Policy Institute. (10/23/2024). Case: 5:24-cv-00304-DCR Doc#:1. U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky. ↩︎