The implementation of CFPB’s Section 1033 rule will likely bring significant cybersecurity implications for financial institutions and third-party service providers within the banking and financial services sector. The final rule, issued October 22, 2024, seeks to provide a roadmap for banks and nonbanks in the sector for rolling out programs to protect consumer data rights. Though the rule has been published, the Bank Policy Institute, in association with other plaintiffs, has filed a suit against the CFPB on several points within the final rule.1 A subsequent blog article will cover this final rule and the emerging conflict it has sparked.

Independent of these developments, today we will be covering the way the CFPB envisions implementing the open banking/open finance mandate it was assigned through Dodd-Frank. That is, it intends to implement the program in concert with private sector consensus-based organizations designated as standards-setting bodies (SSBs).2 The final rule on SSBs was issued on June 11, 2024, separate from the final rule noted above for the other more substantive parts of the Section 1033 program. The SSB rule was more procedural and provided the evaluation criteria for designation as an SSB by the CFPB.

On September 24, 2024, CFPB issued its first notice of acceptance of submittal by Financial Data Exchange (FDX) to become an SSB. FDX is a nonprofit industry standards body operating in the U.S. and Canada.3 It is dedicated to unifying the financial services ecosystem around a common, interoperable, and royalty-free technical standard for user-permissioned financial data sharing called the FDX API.4

FDX has over 200 members, including financial institutions, core banking processors, data aggregators, fintechs, consumer groups, and other financial industry stakeholders. The organization is governed by a board of directors and has over 30 different committees, working groups, and task forces. As of Fall 2024, the FDX recorded 94 million customers, signaling widespread industry acceptance.

There have been 13 public comments on the FDX’s submittal to serve as a recognized SSB as of the time of writing. These comments will be summarized below, but first, let’s cover what it takes to be considered eligible to become an SSB.

Becoming an SSB Under Section 1033

The leadership of the CFPB has long advocated a philosophy of open banking/open finance as the model for the work of the Bureau, building on its mandate from Dodd-Frank for consumer protection. But what is open banking?

At its core, open banking and open finance embody the principle that individuals should have sovereign control over their financial data and the power to leverage it for their benefit. This framework challenges the traditional model where financial institutions act as exclusive gatekeepers of customer data, instead advocating for a democratized financial ecosystem where data flows securely at the customer’s discretion. The theoretical foundation rests on several key premises: that data portability enhances market competition and innovation, that increased transparency leads to better consumer outcomes, and that individuals have a fundamental right to access and utilize their financial information.

This philosophy aligns with broader digital rights movements that view personal data as an extension of individual autonomy. Open finance expands this concept beyond traditional banking to encompass a holistic view of an individual’s financial life (e.g., mortgage loans, automotive financing), recognizing that modern financial services are increasingly interconnected and that artificial data silos can hinder personal financial optimization and broader market efficiency.

However, this openness is not without risk. Even though FDX and the U.S. banking ecosystem have made significant strides in securing the interfaces between data providers (e.g., a bank) and third-party providers (e.g., a mortgage lending entity) with the fit-for-purpose OpenID Connect (OIDC) based FDX API 6.2, there are still questions that were raised by financial institutions, trade groups, fintech companies, consumer groups and others during the proposed rule comment period.

This standard has been widely adopted by the broader community. However, it is such a wide and diverse constituency there are still many disagreements about how best to tackle tough technical issues such as APIs for banking and financial services. Some of the same concerns raised by the community during the proposed rule public comment period have been raised during the public review of FDX’s application to serve as a recognized SSB.

Some of these can be summarized as follows:

- The FDX API 6.x standard was based on OAuth 2.0 & OIDC. However, security leaders within the industry, in conjunction with the OpenID Foundation, have taken it a step further to address the evolving and sophisticated cybercriminal attacks against banking and financial services networks. This is the development of the Financial Grade API (FAPI) Specification 1.0 Advanced Security Profile incorporating advanced cryptographic protocols. FDX has updated the FDX API standard to version 6.2 to incorporate FAPI. Well-resourced financial institutions are advocating for the adoption of this more stringent standard. In contrast, small and midsize enterprises (SMEs) are even challenged with simple implementations like token account numbers for cross-organization/cross-platform data sharing and believe FAPI is unattainable. A wide chasm exists here.

- The 1033 final rule calls for a certification program, and, indeed, FDX has implemented such a program. These are important to guide conformance testing and interoperability. However, recent governance and leadership changes within FDX, in part to qualify as an SSB, have led to a dynamic environment and great uncertainty for the broader community, including how the certification program will unfold under the new rule. Some advocates argue that the certification of qualified parties (data providers and third-party providers as defined by the 1033 rule) should be implemented by a separate, neutral certifying body.

- Some advocates of open banking and FDX’s application have argued that a federated registry for approved parties, both data providers and third parties, be developed to streamline the review and approval process for participation in the ecosystem.

There are strong disincentives by some parties that are heavily invested in legacy information technology infrastructures to adopt open banking, but it is not a new concept. In fact, countries such as Australia, Brazil, England, and the UAE have already rolled out extensive open banking programs. FDX’s efforts to conform to the SSB evaluation criteria and transform itself to accommodate an open banking/open finance mandate have driven many of the governance, operational and procedural changes we are now seeing. Criticism of CFPB and FDX is expected given some entrenched entities, poorly resourced SMEs, and other parties who desire stronger clarity on risk fundamentals, such as prescribing the circumstance or timeframe when traditional screen scraping must end.

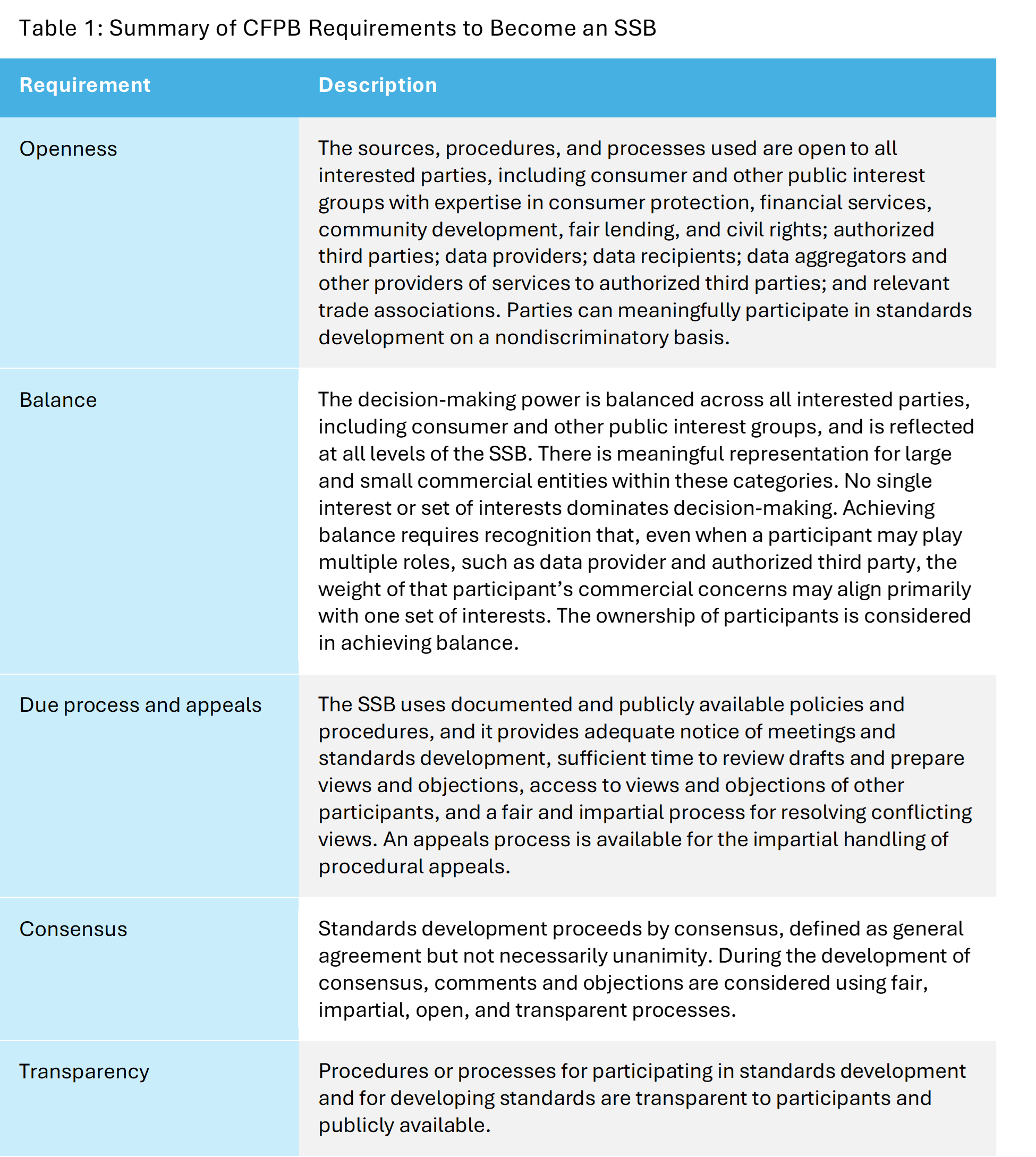

Now on to the to the topic of FDX’s application: Table 1 summarizes the principles and requirements for approval as a standard-setter.

The CFPB also issued a set of guidelines for submitting applications for approval.

FDX’s Application

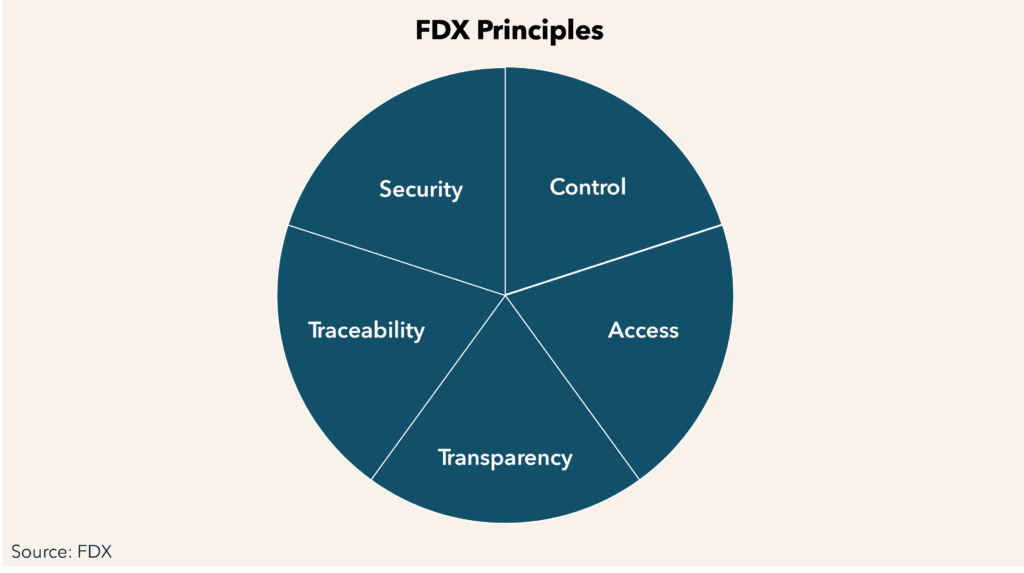

FDX’s five core principles of financial data sharing stem from its years as a standard bearer for information assurance. The principles exhibit a traditional emphasis on security and information assurance (Figure 1).

Figure 1: FDX Principles

To be successful, FDX will need to meld its core principles with the five criteria for open banking/open finance as given in Table 1 above and the final rule from CFPB.

Their application articulates their approach to achieving openness, balance, due process, consensus and transparency. Tests against these criteria are strategic in nature and address governance, compliance, and risk management. In contrast, the pre-existing principles were more tactical, addressing the fine-grain elements of API design, development, documentation and roll-out for widespread adoption and implementation.

They are counting on the widespread adoption of the FDX API 6.2 specification, which includes the following:

- Over 620 different financial data elements covering banking, tax, insurance, and investment data

- Standards for secure authentication and authorization

- User experience guidelines for the financial data sharing journey

- Endpoints and data structures for specific use cases

The last two bullets are above and beyond the scope of Section 1033 rule but were implemented as a result of member and user feedback during the various revisions and refinements to the standard. By developing and maintaining this standard, FDX argued in its application that it is well positioned to function as an SSB as defined by the CFPB to drive open banking adoption in the U.S.

Some of the key governance changes FDX is making are as follows:

- Board of directors composition: There will be two primary voting constituencies with equal voting power—a data provider member group and a third-party provider member group. There will also be two noncommercial board seats and guaranteed SME representation, as well as two reserved seats for Canadian representatives.

- Key decision-making bodies: Board committees (executive steering committee, technical review committee, and strategic planning committee), dedicated councils, working groups, and task forces

The decision-making process includes five key components:

- Uses request-for-comment system for changes to specifications

- Requires a two-thirds majority for material actions

- Includes appeals process for disputed decisions

- Provides documented and public standards/policies

- Ensures balanced representation across all levels of decision-making

The structure is designed to ensure the balance between different stakeholder groups, meaningful representation for smaller entities, and transparent decision-making processes while preventing any single interest from dominating.

Summary of Comments on the FDX Application

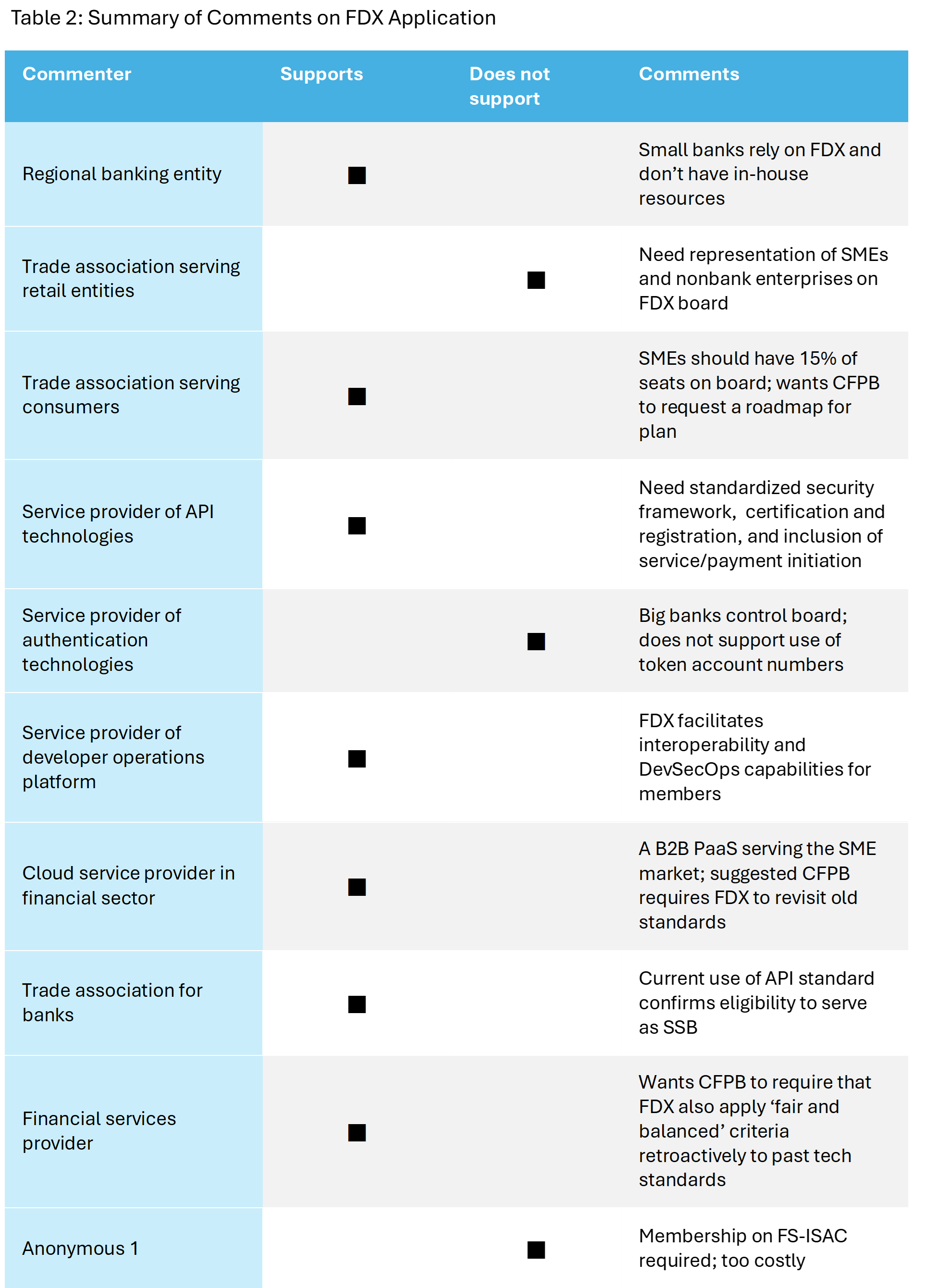

As noted above there have been 13 commentors on the FDX application as of the date of this post.

Those commenters supporting the application argue that FDX has emerged as the cornerstone of open finance standardization in the United States since 2018. With more than 94 million consumer records being exchanged through its API, FDX stands among the world’s leading open finance frameworks. The organization’s governance model, diverse member composition, and stakeholder engagement processes align with or exceed the CFPB’s criteria for SSBs. Recent governance reforms, as noted above, further demonstrate FDX’s dedication to maintaining equitable representation across all stakeholder categories.

However, even those commentors supportive of the application did have some reservations. These are identified in Table 2.

What Now?

The public response to FDX’s application has been mixed. While some stakeholders support FDX’s bid, citing its established presence in open banking/open finance standardization, others have raised concerns about several aspects of its operations. Critical issues include questions about SME representation, the composition and governance of its board, membership costs, technology choices, and whether new standards should be applied retroactively.

The realignment of the organization as separate from the FS-ISAC and a clear delineation of its new governance structure to reflect a broader constituency with more openness and transparency is a step in the right direction. Some commenters would like CFPB to withhold approval until a clear roadmap for implementation of these governance changes is submitted and approved.

The debate on the FDX’s SSB application and the aforementioned lawsuit on the CFPB’s final rule reflects broader industry conflicts, given the wide-ranging and diverse constituency and what is at stake with the Section 1033 initiative. The emerging open banking framework is still quite a fragile construct in the U.S. banking and financial services sector. Let’s see where we go from here.

For more information on the CFPB rules and how your institution may be impacted, contact me at [email protected]. For more information on emerging issues relative to AIP Security, check out the Datos Insights report, Web Application and API Protection (WAAP): Market Landscape and Product Deep Dive, July 2023.

- The case is Forcht Bank NA et al. v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau et al., case number not immediately available, in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky, https://www.law360.com/agencies/u-s-district-court-for-the-eastern-district-of-kentucky ↩︎

- Codified as 12 CFR, Part 1033.141 ↩︎

- Although originally founded by the FS-ISAC, as of September 30, 2024, FDX is a separate 501(c)(6) Delaware corporation with a separate governance and membership structure. ↩︎

- “About FDX,” FDX, accessed October 24, 2024, https://www.financialdataexchange.org/FDX/FDX/About/About-FDX.aspx ↩︎